5 Ways to Make HTTP Requests Using Python

Time to read:

When it comes to software development, there are almost always several different ways to achieve the same outcome. This is true when evaluating a family of third-party software packages, too. For example, in the Python ecosystem there are thousands of packages related to making HTTP requests. Which one should you use?

In this experiment-based tutorial, we’ll walk through brief code snippets that show how to make a simple GET request using 5 of Python’s most popular requests-related packages. We’ll use NASA’s Astronomy Photo of the Day API (shortened to APOD throughout the rest of the tutorial) and open today’s photo in our web browser.

Our goal is to make simple GET requests quickly using a variety of Python packages, rather than to compare and contrast all of the features and subtleties of each package. If asynchronous requests are a better fit for your use case, check out the companion blog post called Asynchronous HTTP Requests in Python with aiohttp and asyncio.

Prerequisites

Locate NASA’s demo API key

Navigate to https://api.nasa.gov/. You’ll see in the Authentication section that you do not need a unique API key to explore the NASA dataset. If you wish to create one anyway, follow the instructions on the webpage and use the API key you’re given instead of the DEMO_KEY we’ll be using.

The rate limits for the demo API key are 30 requests per hour and 50 requests per day, as explained in the DEMO_KEY Rate Limits section of the same webpage. You should be able to stay well within these limits while following along with our HTTP requests experiment. This section of the NASA webpage also states that the string “DEMO_KEY” can be used in place of a real API key value, so that’s what we’ll use in this tutorial.

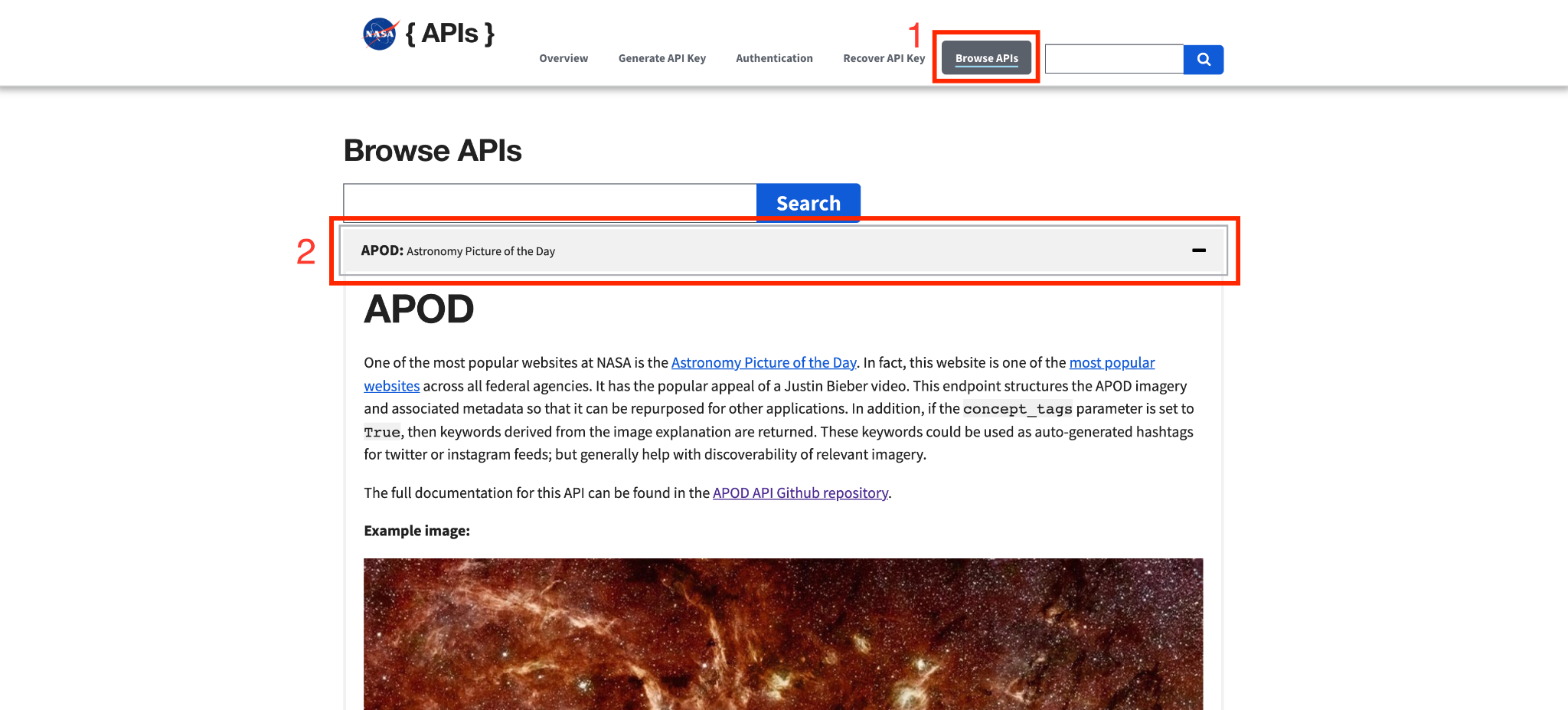

Locate the URL endpoint for the APOD API

The URL we’ll be sending our Python HTTP requests to is https://api.nasa.gov/planetary/apod, which you can find by scrolling down to the Browse APIs section of the https://api.nasa.gov/ webpage and opening the APOD dropdown menu:

If you read the brief information shown in the APOD dropdown, you’ll see that this endpoint accepts only the GET method. This is important because we’ll need to specifically make only a GET request to the endpoint for each of the 5 different HTTP requests we’ll send.

Create the Python virtual environment

Create a new directory for this project called python-http/ in a suitable location on your computer, then navigate to this new directory. In this example, we’ll use the Desktop of a MacBook and create the file from the command line.

Create a new virtual environment for this project so that the dependencies we need to install don’t interfere with the global setup on your computer. To create a new environment called “env”, run the following commands on the command line:

After you source the virtual environment, you'll see that your command prompt's input line begins with the name of the environment ("env"). Python has created a new folder called env/ in the python-http/ directory, which you can see by running the ls command in your command prompt.

Create a file called .gitignore in the python-http/ directory as well. If you're using the command line on a Mac to create the file, this would be the command:

Open the .gitignore file in the text editor of your choice, then add the env/ folder to the contents of the .gitignore file. While we’re here, we’ll also add a line for the .env file we’re going to create in the next section.

Note that the env/ folder created by Python for the virtual environment is not the same thing as the .env file that’s created to store secrets like API keys and environment variables.

Store environment variables securely

API keys are sensitive information and should be protected. Thus, it’s considered a best practice to save API keys as environment variables instead of hard-coding them into your application. We’re going to follow this best practice even though NASA’s demo API key value (“DEMO_KEY”) is public knowledge.

To do this, we can store API keys in a .env file and list the .env file in our .gitignore file (which we’ve already done above) so git doesn’t track it. A .env file is used whenever there are environment variables you need to make available to your operating system.

First, create the .env file. This is the command to run on a Mac's command line:

Next, open the .env file in your favorite text editor and add the following line:

Source the .env file so it becomes available to your operating system, then print the environment variable value to your console to confirm it was sourced successfully:

Install the Python dependencies

In addition to the urllib module that is included in the Python standard library, the 3rd party Python packages we’re going to use for our HTTP requests experiment are:

- requests - Easily the most popular package for making requests using Python

- urllib3 - Not to be confused with

urllib, which is part of the Python standard library - httplib2 - Fills some of the gaps left by other libraries

- httpx - A newer package that offers HTTP/2 and asynchronous requests

Dependencies needed for Python projects are typically listed in a file called requirements.txt. Create a requirements.txt file in the python-http/ project directory:

Copy and paste this list of Python packages into your requirements.txt file using your preferred text editor:

Install all of the dependencies with the command given below, making sure you still have your virtual environment (“env”) sourced.

Create the Python files

It’s time to write some code! Let’s begin by creating a Python file for each module or package we’re going to experiment with:

Code examples are provided below for each of the 5 different files we created. You can also view the project as a whole in this GitHub repository.

To make the examples a bit more robust and useful, we’ll work with two built-in Python modules called json and webbrowser so we can open the Astronomy Picture of the Day in the web browser.

5 popular ways to make Python HTTP requests

1: Requests

The Python requests package is so popular that it’s currently a requirement in more than 1 million GitHub repositories, and has had nearly 600 contributors to its code base over the years! The package’s clear and concise documentation is almost certainly responsible for its widespread use.

Copy and paste this code snippet into the use_requests.py file:

In the example code above, we first import all the modules and packages we need. Then, we retrieve the API key we stored in the .env file (Line 8) and insert it into the URL we’re going to send the GET request to (Line 9). Line 13 is where we use the Requests library, and you can see how simple the syntax is. After isolating the photo’s URL from the API’s response, we open it in the web browser on Line 16.

Because a function call is included at the bottom of the file, you can run this file and the photo should automatically open in your web browser! Run the file in your command line to try it yourself:

2: urllib3

Despite the similarity in names, urllib3 is a 3rd-party package and is completely different from urllib, which is part of the Python standard library. There are more than 650,000 GitHub repositories that list urllib3 as a requirement which make it a massively popular alternative to the Requests library.

Copy and paste this code snippet into the use_urllib3.py file:

In the example code above, we first import all the modules and packages we need. Then, we retrieve the API key we stored in the .env file (Line 8) and insert it into the URL we’re going to send the GET request to (Line 9). On Lines 13 and 14 we make use of the urllib3 package, then process the response to extract the photo’s URL and display it in the web browser.

Because a function call is included at the bottom of the file, you can run this file and make sure it works.

Tip: If you get an error like [SSL: CERTIFICATE_VERIFY_FAILED] certificate verify failed: unable to get local issuer certificate while trying to run the file, follow the steps in this StackOverflow thread to resolve it.

3: httplib2

The httplib2 package is a requirement of 86,000 GitHub repositories. Usage of httplib2 is well behind that of the Python Requests and urllib3 packages, yet httplib2 fills in some of the gaps that are left by the two more widely used alternatives. For example, httplib2 supports persistent connections and caching.

Here’s a simple example of how you can use httplib2 in your project. Copy and paste the following code into use_httplib2.py:

In the example code above, we first import all the modules and packages we need. Then, we retrieve the API key we stored in the .env file (Line 8) and insert it into the URL we’re going to send the GET request to (Line 9). On Lines 13 and 16 we make use of the httplib2 package, then process the response to extract the photo’s URL and display it in the web browser.

Because a function call is included at the bottom of the file, you can run this file and make sure it works:

4: httpx

The httpx Python package is the newest one on our list. It supports the HTTP/2 protocol and asynchronous requests in addition to the standard synchronous HTTP/1 protocol. It’s built to be very “Requests-like” and mirrors a lot of the code patterns present in the Requests package (the first one we covered).

To give httpx a try, copy and paste the following code into the use_httpx.py file:

In the example code above, we first import all the modules and packages we need. Then, we retrieve the API key we stored in the .env file (Line 8) and insert it into the URL we’re going to send the GET request to (Line 9). Line 13 is where we use the httpx library, and you can see how simple the syntax is. After isolating the photo’s URL from the API’s response, we open it in the web browser on Line 16.

Because a function call is included at the bottom of the file, you can run this file and the photo should automatically open in your web browser! Run the file in your CLI to try it yourself:

5: urllib

Compared to how easy it is to make Python HTTP requests with the Requests package in the section above, using the built-in urllib module is a bit more complex. It requires the use of a context manager as well as decoding the response — two things that are generally abstracted away from the developer when using one of the packages in our tutorial.

Copy and paste this example code into the use_urllib.py file:

In the example code above, we first import all the modules and packages we need. Then, we retrieve the API key we stored in the .env file (Line 7) and insert it into the URL we’re going to send the GET request to (Line 8). On Line 12 we create the Request object using the urllib module, and on Line 13 we use a context manager (with...) to send the request to the APOD endpoint and save the response. On Line 14 we decode the response and convert it to JSON, then extract the photo’s URL and open it in the browser on Lines 15 and 16.

Because a function call is included at the bottom of the file, you can run this file and make sure it works:

Congratulations, you just made a GET HTTP Request in Python!

Nice job working through this tutorial! You just learned how to:

- Store API keys and other secrets safely in a .env file

- Make a GET request in Python to an API endpoint in 5 different ways

- Open images from your Python script in your web browser

Next steps for experimenting in Python

To extend our experiment of making HTTP requests 5 different ways using Python, you could:

- Try out some other HTTP-related and request-related packages that are listed in PyPi.

- Do some research of your own to compare the pros and cons of each of the packages used in this tutorial.

- Choose one of the packages we covered in this tutorial and use its documentation to make more sophisticated types of HTTP requests, like one that uses caching.

- Try making POST, PUT, or DELETE requests with an API that supports these methods.

Or, check out some of the other tutorials on the Twilio blog for ideas on what to build next:

- Asynchronous HTTP Requests in Python with aiohttp and asyncio

- 5 Ways to Make HTTP Requests in Node.js

- Expose a Local Django Server to the Internet Using ngrok

I can’t wait to see what you build!

August is a Software Engineer of Technical Content on Twilio's Developer Voices team, specializing in Python. She loves Raspberry Pi, real pie, and walks in the woods.

Related Posts

Related Resources

Twilio Docs

From APIs to SDKs to sample apps

API reference documentation, SDKs, helper libraries, quickstarts, and tutorials for your language and platform.

Resource Center

The latest ebooks, industry reports, and webinars

Learn from customer engagement experts to improve your own communication.

Ahoy

Twilio's developer community hub

Best practices, code samples, and inspiration to build communications and digital engagement experiences.