Your Phone, Your Call - Part I - Eliminating Robocalls

Time to read:

All of us have had the experience. A meeting or a dinner interrupted by our phone ringing with some random number on the screen. Click ‘ignore’. Maybe a minute later we get the notification of a new voicemail (maybe in another language) touting a new deal on satellite TV, or better yet, alerting you to an urgent "lawsuit from the cops." Or rather, they don't leave a voicemail at all... because they'll just robocall you again in 20 minutes, hoping you'll answer from a different random number.

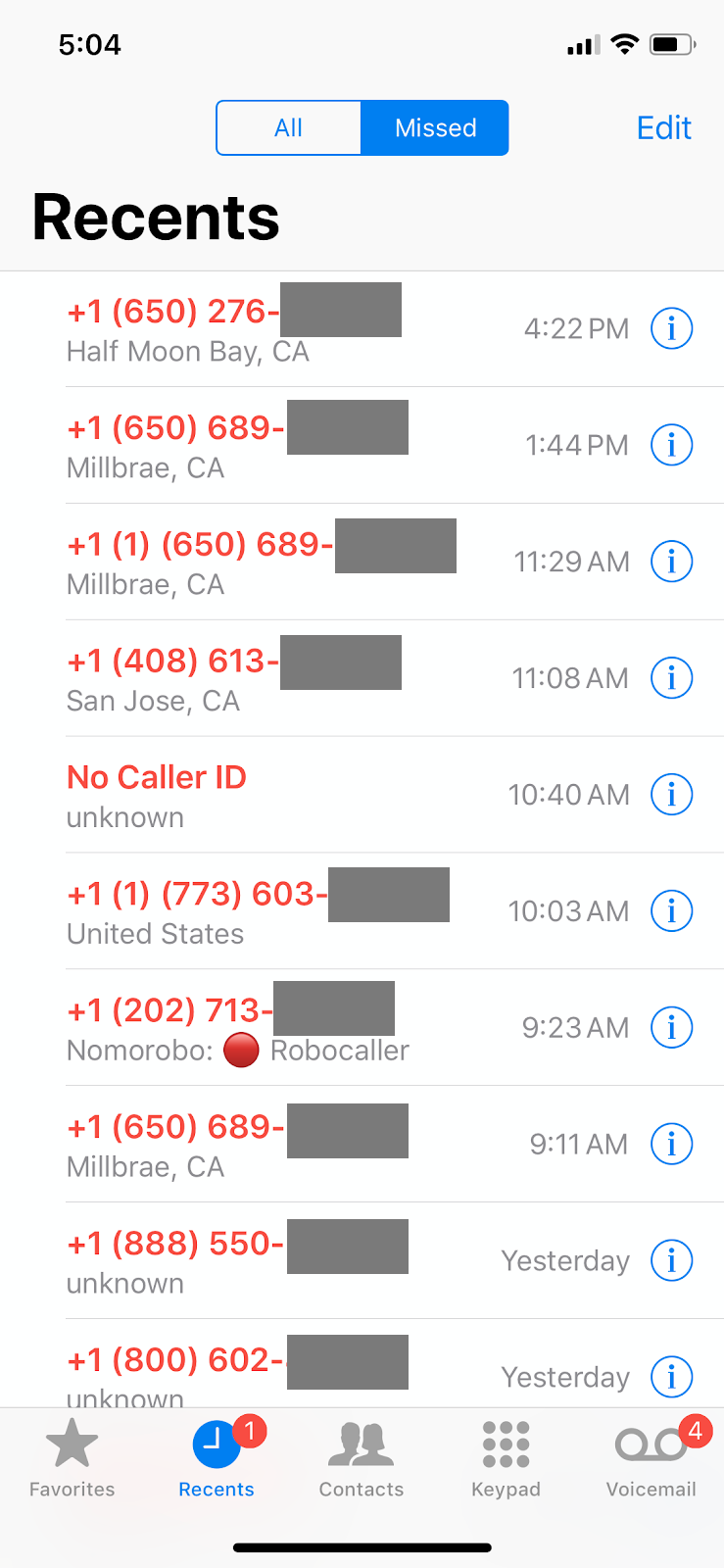

Sound familiar? If your experience is anything like mine, your "missed calls" screen looks a bit like mine:

Robocalling has reached epic proportions and we're all starting to hate our phones. In fact, according to First Orion, nearly 50% of all US mobile calls made in 2019 are expected to be robocalls. Stop and think about that for a second: half of all calls are unwanted.

Since the pervasiveness of robocalling has exploded in the last year, folks have asked me my thoughts, and frankly, whether Twilio allows this with our platform. We don't, and I'm as concerned as you are about robocalling. We don't want these robocallers on our platform, and we actively work to prevent these perpetrators from making unwanted calls using our product. Yet a simple Google search will show plenty of companies actually advertising their robocalling services!

Clearly something must be done.

Why is it so bad?

The root cause started over a century ago…

When the first US telephone services were created around the turn of the 20th century, one company, the Bell Telephone Company (later rebranded AT&T) not only built and operated the network but also every device attached to the network. In that world, trust wasn't an issue because every device was sanctioned by the same company.

But that started to change in 1956 when the DC Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the network needed to be open, forcing AT&T to allow 3rd party devices on the network. And thus began the trend toward more open communications. In 1968, AT&T was ordered by the FCC to allow 3rd party phones to attach to their network. In 1982, the DOJ split AT&T into multiple competitive companies. Fourteen years later, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 made communications even more competitive enabling the creation of competitive local carriers.

At each step, consumers have generally received better service and lower prices through increased competition. So what's the problem?

That original network, designed in the first half of the 20th century, was built and operated by one company. Any actor on the network was automatically and fundamentally trusted. That meant that little security was built into the network itself.

But with all the breakups and competitive tides the network became more open. However, the underlying protocols – and trust – were fundamentally based on a 100-year-old model. There was no way to anticipate the technological advances that would dramatically change everything about telecommunications in the coming decades.

Roll ahead to 2019: if you have the right access, hardware and/or software -- you can initiate a call on the network, from any phone number, to any phone number in a (pretty much) untraceable way.

Vrrrrrrp? Record screech. What?!? That's right… anybody can impersonate anybody else on the phone network to make a phone call. (Yeah, I was surprised to learn that too.)

Twilio’s Perspective

When we started Twilio in 2008, I was a software developer who knew nothing about telephony. We realized that software developers like ourselves needed to build communications into apps -- so we started down the path of figuring out how to make a phone ring.

As a software and web developer raised with the Internet as my development background, I had certain assumptions about how trust and security work on networks: boundaries between trusted and untrusted networks, separation between layers of the stack, and so forth. And, I have to admit, when we first started learning about how telephony worked I was amazed at what the network would permit you to do. It seemed like absolute, utter, chaos, mitigated largely by good intentions. So we built a number of protections into Twilio's products to close what seemed like security holes you could drive a ${large_wheeled_vehicle} through.

We require you to confirm ownership of a phone number before you are allowed to use it as "caller-id" when initiating a phone call via our APIs. By default, we bill by the minute, not the second, to deter short duration calls and impair the economics of robocalls. We’ve also built fraud protections into our product, such as geographic permissions that disable calls to high fraud destinations which are rarely used for legitimate use-cases. We also have default throughput limits, so an organization that just signed up yesterday can’t place a high volume of calls or send a high volume of messages immediately. All of these safeguards (and more) are features we added to prevent malicious actors from using Twilio.

All of this is on top of our Terms of Service and Acceptable Use Policy, which expressly prohibits "using the Twilio Services in connection with unsolicited, unwanted or harassing communications (commercial or otherwise), including, but not limited to, phone calls, SMS or MMS messages, chat, voice mail, video or faxes." We use artificial intelligence and other instrumentation to look for patterns that might indicate abuse.

However, there are many competitive local carriers who have access to the telephony network, both inside the United States and outside. And in a world of untrusted devices plugging into a trusted network, it takes just a small handful of bad actors engaging in shenanigans to ruin the network for everybody.

Your Phone, Your Call.

We believe the next step is to put you back in control of your phone, where the communications industry provides the tools for you to receive only wanted communications from trusted parties. You’ll see a cryptographically signed caller-id asserting the company or person who's initiating a call to you is who they claim to be. In addition, ideally, your phone will only ring if a caller's reputation is up to par. To achieve this vision, illegal spoofing needs to be eliminated and a strong notion of identity needs to be established.

This is not unlike the status of email, circa 2002. Back then, you could send an email as anybody -- you just put their address in the From: field, and your mail server delivered it. It's true, a friend didn't believe me back in 2000, so I sent him an email from "bgates@microsoft.com" and he was blown away -- what a hacker I was!

Clearly, the industry realized this situation wasn't sustainable and email spam was growing. So some smart people came up with some smart solutions to cryptographically sign emails and specify allowed IP addresses to send on behalf of a domain: DKIM and SPF.

Anti-spam technology within email has continued to evolve to address the emerging problems of phishing and other malicious attacks. DMARC is a DNS-based policy allowing domain owners sending email to give a set of instructions to receiving domains on how to treat email that fails either SPF or DKIM. As a result, the amount of spam we receive today is a tiny fraction of what we got 15 years ago and companies have ways to protect their reputations and their customers from malicious actors trying to impersonate legitimate businesses for nefarious purposes.

For phone calls, there's some good news. Some very smart people have been working on new ways of cryptographically signing calls – a digital signature – proving ownership of a phone number before the call is initiated. One example of this is a new protocol called STIR/SHAKEN, which the communications ecosystem is working on now. Before any authentication method can be impactful at scale, it needs to be adopted by a broad swath of the ecosystem. Twilio is fully committed to efforts to authenticate calls so the identity of callers can be proven, and it looks like STIR/SHAKEN is a good candidate to do just that.

But once you know the identity of the caller, what should you do about it? That’s where reputation comes into play. Once you know the caller isn’t pretending to be someone they aren’t, how do you (or a system working on your behalf) decide if your phone should ring, or if you should answer it? This is the next challenge, and so we'll explore identity and reputation in our next post...

Your Phone, Your Call - Part II - Why did we have caller ID in the 90s but not today?

Jeff Lawson is the Founder, Chairman and CEO of Twilio. He's focused on restoring trust in the communications we rely on everyday so that you can answer your phone again. He can be reached on Twitter at @jeffiel.

Related Posts

Related Resources

Twilio Docs

From APIs to SDKs to sample apps

API reference documentation, SDKs, helper libraries, quickstarts, and tutorials for your language and platform.

Resource Center

The latest ebooks, industry reports, and webinars

Learn from customer engagement experts to improve your own communication.

Ahoy

Twilio's developer community hub

Best practices, code samples, and inspiration to build communications and digital engagement experiences.